Athanasia Safitri

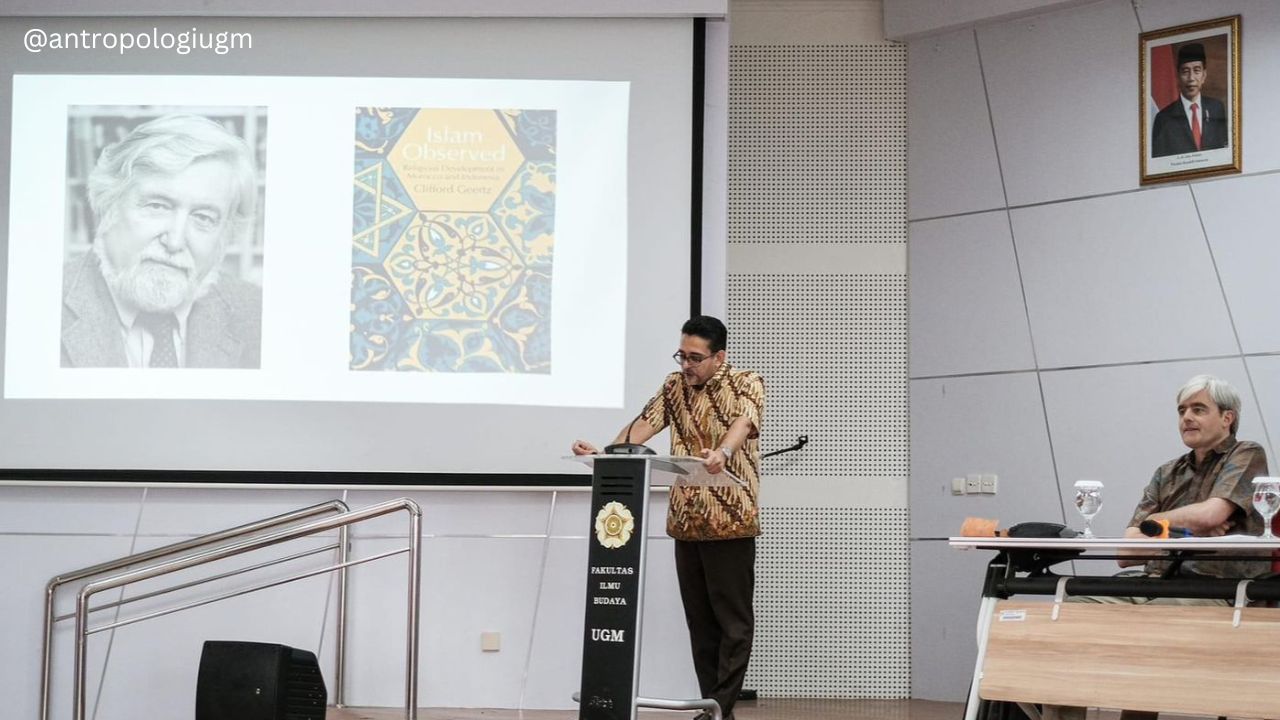

The Department of Anthropology, CRCS, and ICRS of UGM collaborated to hold a seminar entitled "Islam, Ambiguity, and (In)Tolerance: Anthropological Perspectives from Southeast Asia" on August 14, 2024 with Ismail Fajrie Alatas (Associate Professor of Middle Eastern & Islamic Studies, and History, New York University) and Martin Slama (Senior Researcher in the Austrian Academy of Sciences) as speakers.

Alatas stated that there has been an ongoing project to publish a book on the cases and experiences regarding Islam, ambiguity, and tolerance, of which he and Slama will introduce the topics. In this seminar, he presents existing theories that highlight the development in the anthropology of Islam and Slama elaborates with the perspective from Southeast Asia.

Their main argument lies in the forms of ambiguity in Islam experienced in Southeast Asia which grow along with different interpretations in tolerance leading to both harmony and conflicts. They underline the debates appearing over particular Islamic discourse or practice and whether there is an urgency in offering contemporary discussions and thoughts on Islam, ambiguity, tolerance, and intolerance to the public.

Islam and ambiguity

Alatas started by claiming that anthropology of Islam has expanded the scope of Islamic study to the extent of highlighting the various socio-cultural and economic relations that shape Islam as a living reality. It changes the interpretation of Islamic textual traditions and observes the everyday practice of the religion to understand Muslim life realities. He continued, saying that early anthropologists studied Islam to generate the general theory of religion, mentioning Clifford Geertz, who states in his book Islam Observed (1968) that an anthropological study of Islam is a way to understand the “machinery of faith”.

Alatas also remarked that Ernest Gellner in his book Muslim Society (1981) suggests that Islam is a coherent social blueprint which arranges how people should live in society through certain rules and norms which then leads to a stable social structure. These two anthropologists have been criticized for neglecting the way Muslim should represent themselves and practice Islam. One of the critics is Talal Asad in his work Genealogies of Religion (1993) who points out that power creates religion and that Islam must be seen as a continual process which can be developed or changed by institutional relations, authority conditions, as well as political, economic, and social situations.

Alatas then referenced Shahab Ahmed’s What is Islam? (2016) and Thomas Bauer’s A Culture of Ambiguity (2021) which show the importance of contradictions and ambiguity in pre-modern Islamic discourse. Ahmed argues that when exploring interpretations, all contradictions require periods of time for reflection by the believers, while Bauer focuses on how cultural differences produce various responses to ambiguity. Alatas noted that they both describe modernization as a process which increases intolerance, and annihilation of ambiguity.

Adjustment to tolerance and intolerance

Related to the forms of ambiguity in more recent Islamic discourse in Southeast Asia, Slama focused on the practice of Islam in Java. Slama discussed Clifford Geertz’s The Religion of Java (1960) which underlines a colonial perception of Islam in Southeast Asia that has its origins in earlier colonial descriptions in the 19th century. Geertz suggests that there is both tolerance and intolerance that is explicitly attributed to Javanese people, especially among the Javanese upper class called priyayi.

Slama continued by discussing the paradox of tolerance, coined by Karl Popper in his book The Open Society and Its Enemies (1994), which shows that unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance; in order to encourage the tolerant to be intolerant to those who are intolerant. Islam is regarded as the source of intolerance in Java in two distinct ways: there are Javanese who have become intolerant because of their religious zeal, and there are also Javanese whose intolerance is precisely directed against the former.

Slama then discussed Koentjaraningrat’s interview with the Jakarta Post (1995) wherein he mentioned that the Javanese tolerated accepting the Indonesian language (Malay at that time) as the national language despite the fact Javanese is spoken by the majority and used in the most ancient literature in Indonesia. However, he also indicated that many tolerance practices in Java have negative side effects as in the values of gotong royong (mutual benefits), solidarity and kekeluargaan (family spirit) which are good but can also make people less independent since they rely so much on others’ assistance. He continued that a society characterized by strong social hierarchies and authoritarianism may exhibit high levels of tolerance.

Primordialism in Islam has shown ambiguity which can be domesticated to avoid modernization. Today’s challenge appears in the perception that Islam is not actually ambiguous but that people may have tolerance and intolerance to this ambiguity of Islamic teachings. Furthermore, both researchers suggest that the study of Islam needs to study everyday practice since ambiguity can be only seen and experienced at the grassroot level, leaving the elite to remain coherent. Further studies must return to the roots of Islamic studies while exploring this ambiguity and contradiction.